|

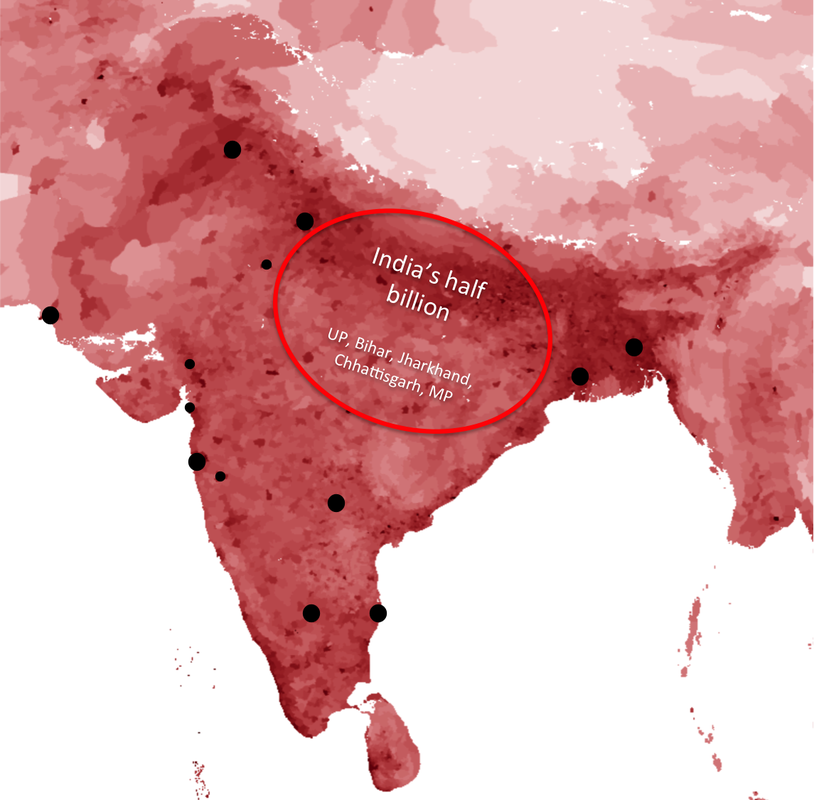

The Hindi speaking provinces of India: Uttar Pradesh (UP), Bihar, Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh and Madhya Pradesh (MP) together make a population close to half a billion [1]. Historically, this region was home to important cosmopolitan cities of the world, like Kashi and Patliputra. Just over a hundred years ago, four of the ten largest cities (Lucknow, Banares, Kanpur and Agra), and eight of the twenty largest cities in India (+ Allahabad, Patna, Bareilly and Meerut) were in the region (1911 census). But today, the region suffers from a “metropolis vacuum”, because it has no major metropolitan agglomeration to attract talent and investments.

The six largest cities of India, Delhi, Mumbai, Kolkata, Chennai, Bangalore, and Hyderabad all lie outside of this Hindi heartland. The other new upcoming urban centers like Pune, Ahmedabad, and Surat also lie outside of the region. Among the ten largest cities none are in the region, while only five cities (Lucknow, Kanpur, Indore, Bhopal and Patna) belong in the top twenty (2011 census). The glaring absence of a major metropolitan center in the region has forced young people to migrate away from the small towns and move to other cities in the West and the South. Today, India needs sustained double digit economic growth (Financial Times, 2015), to fulfill the aspirations of its highly ambitious and very young population. During the previous decades, India’s growth was primarily centered in its West and the South. But, if today India aims to sustain and accelerate its progress, the Hindi heartland needs to become an engine of growth too. Can such growth happen in the absence of a metropolitan anchor? Cities play an indispensable role in any region’s economy. If we consider the historical rise of Europe, cities like Amsterdam and London played an indispensable role in its progress. At the end of the fifteenth century, Northwestern Europe was not very different from parts of India or China. Yet the region leap-frogged ahead of the historically dominant economies of Asia, as Northwestern Europe underwent a “bourgeois” revolution (McCloskey 2016) in the sixteenth century. In this region, cities such as Amsterdam, Hamburg and London at the Atlantic coast, established rules-based-markets (Ogilvie 2011), and they attracted trade, talent and capital. This agglomeration helped in the development of a bourgeois city dwelling class that saw investment in learning and enterprise (and not land and nobility) as the path to progress. Eventually, the Northwestern European region developed a distinct culture of growth (Mokyr 2016), as innovation became more frequent (either through invention or imitation) and profit making became more desirable. As rulers found new ways to generate revenue, they facilitated the formation of joint-stock-companies like the English East India Company, which traded overseas, and eventually this process of innovation and commerce (often along with colonization) culminated in the Industrial Revolution, which first was sparked in eighteenth century England. Nobel laureate Robert Lucas (2018) in his recent research has emphasized the importance of cities in the industrial revolution. Cities match capital with talent. Cities that are accessible (not controlled by a clique of business and political elites) and cosmopolitan (not hostile to particular groups of people) attract capital and bring people of diverse backgrounds and talents together to form productive partnerships. Such cities motivate people from nearby areas to learn new skills and to invest more in the education and health of their children. In India, we can see this historical process of growth happening in real time, with the meteoric rise of Bangalore. In 1911 Bangalore was only a minor city in India. Today it ranks third, thanks to an environment that is welcoming to entrepreneurs, innovators and investors. What happens in regions like the Hindi heartland, which lack major cosmopolitan cities? In such regions capital and talent are matched much less efficiently. If people do not expect that their talent will be rewarded because of this mismatch, they have lower interest in investing in themselves and their children. The mismatch creates a vicious circle of low human capital and low growth. Such vicious circle where people don’t have hope for a better future, creates a fervent ground for anti-social behavior, like lynching and vigilantism. The Hindi heartland needs a few major cities, to get out of this vicious circle. When discussing Indian economic growth, much emphasis is given to India’s central government. India’s central government plays a very important role in pushing for the much-needed reforms, which can make the match between capital and talent more efficient. But India’s state governments and even more locally – the mayors and their municipal councils are key players in shaping the direction of India’s regional development. If India’s Hindi heartland is to grow, it needs state governments and municipal councils that appreciate the importance of large and cosmopolitan cities in economic growth. India’s central polity, both on the left and the right, understands the importance of cities in economic development. But is it concerned about the metropolis vacuum that is diminishing the prospects of India’s Hindi heartland? Recently, India has made plans to develop industrial corridors connecting its major cities. The Delhi Mumbai Industrial Corridor (DMIC) has received much attention in the media, which connects the two cities via western cities like Jaipur, Ahmedabad, and Surat. Such projects offer much potential for future economic growth. Yet, if Indian policymakers are serious about ending the metropolis vacuum faced by its half a billion citizens, they should take concrete and targeted steps to accelerate urban development in the region. The Amritsar-Kolkata industrial corridor is a useful step, and more projects focused specifically on the heartland are needed to remedy this metropolis vacuum. The good thing about urban growth is – cities grow by themselves – as long as the local governments “facilitate” adequate urban public goods (like roads, water, electricity and public transport) and establish a rule of law, which develops a favourable environment for all enterprises, not a chosen few (i.e. they are pro-market not pro-business, see Rajan and Zingales, 2004). Partly, the stagnation of cities in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar is because of the absence of an unbiased rule of law, which should be blind to a person’s party, ideology, religion, caste or class. Which entrepreneur will like to settle in a city, where the government’s attitude towards you and your business can change as quickly as the climate? It is also important to fix accountability and urban governance by empowering local mayors. Indian cities suffer from severe handicaps due to poor urban governance (Janagraha ASICS 2017). Cities around the world, from London to Chicago have influential mayors, and residents hold them responsible if the city fails to function well. When heavy rains clog cities like Patna, who is to be held accountable? The government of Bihar which represents ten crores (hundred million) people, or a local mayor? The answer to this question should be clear, so that we can stop passing the buck. Targeted steps to rejuvenate cities of Hindi heartland are a win-win for all stakeholders in India’s growth. If metropolitan cities can emerge in the region, it will relieve the migratory pressures many growing cities like Bangalore are facing today. Here is the bottom-line: Of the 1.35 billion people of India, about half a billion cannot be left behind. An urban policy that emphasizes healthy growth of cosmopolitan cities throughout India including its Hindi heartland is a crucial ingredient for achieving sustained two-digit GDP growth, which India acutely needs. [1] 475 million in 2018. (220 mm in UP, 110 mm in Bihar, 80 mm in MP, 35 mm Jharkhand, 30 mm Chattisgarh) Financial Times 20: https://www.ft.com/content/a44b8f48-be61-11e4-a341-00144feab7de McCloskey, Deirdre N. Bourgeois equality: How ideas, not capital or institutions, enriched the world. Vol. 3. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016. Ogilvie, Sheilagh. Institutions and European trade: Merchant guilds, 1000–1800. Cambridge University Press, 2011. Mokyr, Joel. A culture of growth: the origins of the modern economy. Princeton University Press, 2016. Lucas Jr, Robert E. "What Was the Industrial Revolution?." Journal of Human Capital 12, no. 2 (2018): 182-203. Rajan, Raghuram G., and Luigi Zingales. Saving capitalism from the capitalists: Unleashing the power of financial markets to create wealth and spread opportunity. Princeton University Press, 2004. Janagraha ASICS 2017: http://janaagraha.org/asics/ASICS-2017.html

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Prateek RajPersonal blog. Views expressed are my own, expressed in personal capacity. Archives

May 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed