|

Reign of tradition

A traditional society revers the wisdom of the ancestors. In the earliest period of human history, the pace of growth was slow, and traditions- or received wisdom from ancestors - were good pointers on how one should behave. Not all traditions were fair. Some like the caste of system or feudalism were atrocious. But in an era where change was slow, these traditions (good or bad) were persistent. It was difficult to mount a revolution. That is why, we do not hear about revolutions in the ancient past that very much. We hear about the American or French Revolutions in the eighteenth century, or about the Indian independence movement since the nineteenth century, or if stretching to the sixteenth century, we hear about the Protestant Reformation. Why did revolutions against established traditions become common in the early modern era? It was difficult to coordinate hundreds of thousands of people together to mount a mass rebellion against a dominant group. So, technologies such as the printing press, that emerged in the fifteenth century, became important coordinating technologies, as they could print pamphlets and books for call to action. So, traditional society began to lose its grip only once technological and economic progress began. As lives of people transformed within generations, traditions that were passed down from one generation to the next were no longer good guides of behavior. What replaced tradition in this era of rapid change? It was rationality. Rise of Rationality While Asian civilizations were at the helm of progress for much of the human history, Europe began to catch up in the modern age. Economic historian Joel Mokyr says that the key difference between early modern Europe and elsewhere was the lack of reverence to ancestors. As Europeans travelled in the age of exploration, and read ancient books, they discovered the gaps in knowledge of their ancestors. They began to question ancestral wisdom, and began believing that their generations may very well be smarter and wiser than the past. When such a break from tradition took place, something needed to replace the guidance of tradition? In place of tradition people began to think for themselves, individually, and began relying on their rational faculty. The ancient world had no dearth of rational thinkers. In Hindu traditions two of the six schools- Nyaya and Vaisheshika rely heavily on logic to learn about reality. But in traditional societies, such logical schools faced tough competition from schools that relied on rituals and traditions, where testimony was highly valued. In the modern age, testimony from ancient texts and ancestors is given much less credibility than testimony of the peers, and inferences of one’s own mind. Such a system that emphasizes peer and rational learning inevitably gave rise to the scientific method. It should not come as a surprise that rise of rationality gave rise to an Age of Enlightenment and science in the seventeenth century. Stalwarts like Newton and Darwin revolutionized human understanding of the world around us. But with such “enlightenment” and rationality came dark realities. As Europeans, became more technologically advanced, they left a trail of exploitation around the world. India faced several famines during the colonial misrule. Unchecked power of European technological superiority was especially devastating for ordinary Europeans themselves as they fought two cataclysmic world wars. Nazis, fueled by pseudoscientific ideas of a Darwinian race war, perpetrated unspeakable atrocities including the Holocaust that systematically killed millions of Jews. So, age of rationality, despite its ability to bring rapid technological and economy progress, reached a nauseating conclusion during the World War 2, characterized by devastation, genocide and moral bankruptcy at a scale unheard of in human history. How could rationality culminate in such a devastating end? Because it was devoid of morality and empathy, and especially devoid of a concern for human dignity. Primacy of Dignity Consider the founder of modern statistics - Francis Galton. He was a polymathic genius who gave the world regression and fingerprints. But he was also the founder of eugenics, and believed human races were inherently different, and like breeds of animals, each race had unique characteristics that were hard baked by nature. Eugenics, an idea that was further popularized by the Nazis, believed in designing a better race using scientific principles, where the ideal race was the Nordic-Aryan ideal. In name of such improvement of racial stock, “impure” and “inferior” groups like the Jews, or “defective” people like those who were disabled or belonged to the LGBT community, were killed in gas chambers in a highly bureaucratic and organized operation. While the Nazi obsession with a purity may seem like a perversion, but such ideas of group superiority were not exclusive to the age of rationality. Traditional societies were far from egalitarian. Gender, religious or caste discrimination was rampant is such societies for long, with fetishized notions of purity and pollution playing an important role in regulating conduct. Twentieth century saw rapid expansion in human rights. The second world war could not have been won, without the contribution of armies made of people of color, and of factories run by women. After the end of Second World War, there was a greater reflection on the perils of Nazism type ideologies that failed to acknowledge human dignity. In the 20th century, women sufferage movement, civil rights, Dalit, LGBT and the several independence movements, most prominently in India, brought representation to the marginalized groups. As their voices were heard more, reason in itself was no longer an appropriate guide for decision making. It had to be coupled with the notion of dignity. For example, John Rawls in his pathbreaking book on Justice, provided a framework that combined reason with dignity. He said, we should design a society keeping a veil of ignorance about where we as individuals would be positioned in such a society. If this principle of veil of ignorance gets applied, it is difficult to advocate for lesser rights for marginalized groups, and rights and laws become more inclusive and universal. Consider the notion of “men” in the American constitution, which has evolved from including only land owning white men in eighteenth century, to all humans in the twenty first. Conclusion In a traditional society, all people had a “proper” place. Consider the position of transgenders in Indian society. While being a transgender was tolerated in Indian society, and at times transgenders were even worshiped, but the social and economic roles they could take were severely limited. As societies became more rational, it did not spontaneously create an inclusive society. Labeling of “proper” and “improper” humans became common. For example in Victorian England, the rights of LGBT persons were severly curtailed, and anti-LGBT laws and sentiments diffused in other colonies. However, in the modern era human dignity is more important than reason or tradition, and in this era we need to empathize, stand in other people’s shoes and question if it is the job of society to dictate what is the “proper” thing for people to do. This tradition of empathy, and primacy to dignity, gives a simple solution: we must design a society which gives all people the freedom to decide what is proper for them. If a person’s life decisions do not directly affect our own, should we decide on their behalf what is “proper” for them? Similarly, when people’s individual decisions affect others, should some stakeholders take decisions for the rest? A fully realized society, that gives primacy to dignity, and tests both rationality and tradition on that anvil, naturally offers universal fundamental rights to all people, and develops participative and democratic systems of collective decision making. The ideals of such a society are codified in great constitutional texts such as the the American and Indian constitution. Though these constitutions codify great and noble ideas and are great achievements of mankind, the application of these ideas nonetheless depends on those who practice and apply them in their daily lives. Do we give primacy to human dignity, and test our traditions and rationality on that anvil? Or are we comfortable in defending our traditions or reasoning even when they violate the dignity of fellow human beings? The answers to the questions above will eventually decide the fate of our society in the long run.

1 Comment

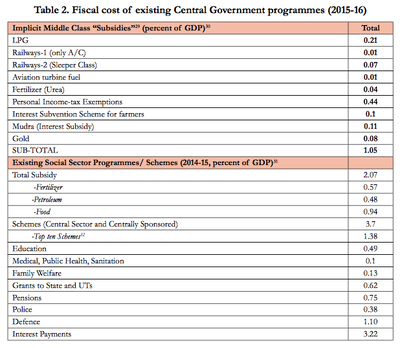

Source: Economic Survey of India 2017 Source: Economic Survey of India 2017 Basic income has been a topic of intense scruitny in India over the last few years. 2017 Economic Survey even wrote a report on Universal Basic Income (UBI) and its feasibility. Political parties across the spectrum have been toying with the idea. A minimum income guarantee scheme like NYAY (Nyuntam Aay Yojana) that has been proposed by Indian National Congress is a difficult to implement but a feasible scheme, contrary to the emerging narrative that its an impossible and unfeasible idea. Middle class in India gets 1% of GDP as yearly subsidies from GoI. Total subsidies by GoI amount to 2% of total GDP, and much of it is subsidy given on food. GoI's social sector schemes cost 3.7% of yearly GDP (not including the 2% subsides). A basic income scheme such as NYAY scheme which covers 20% of poorest households, will cost 2% of the yearly GDP. It is not at all in the impossible terrain. Funding a basic income scheme that costs 2% of the total GDP is especially feasible in an economy that grows at 6-8% each year. This implies that a fraction of gains that India makes each year go to the poorest Indians. The proposal that 20% of India's population should be guaranteed 2% of India's GDP is not a radical idea. Such a scheme is also inevitable, as cash transfers become easier, and it will not come to me as a surprise if BJP were also mulling over similar ideas (afterall the UBI report came under their government, and they proposed a minimal basic income for farmers). It is also important to consider that a basic income format of welfare was simply not feasible in a pre-IT era. A basic income based social welfare has become a possibility because of two key innovations that characterize India's development in 2010s: 1) development of a robust framework of universal identity (UID/Adhaar) system and online and mobile banking infrastructure, and 2) significant exapansion in bank access for people. However, NYAY is just one proposal. There are many alternative ways of distributing basic income. There are three questions that need to be considiered when discussing basic income as a policy:

Personally I am of the view that social welfare schemes should be as universal and unconditional as possible (although not always feasible), because implementing targeted and means-tested schemes open up a backdoor for inefficiency, bureaucracy and corruption. Bo Rothstein has a fantastic book on Quality of Government, which promotes the notion of impartial governance. So, I tend to favour basic income schemes that are universal and unconditional (hence a UBI), and at the same time do not completely substitute some in-kind welfare schemes like healthcare and education. I believe policies targeting the poor, should provide some income relief through cash transfers as a UBI, but other forms of in-kind relief (such as accessible healthcare, education, housing and amenities) cannot be replaced. Social welfare should still be seen as a basket of programs, which aid people in their incomes (yes), but also in their consumption. Note: If I designed a basic income scheme, it will target childhood inequality by developing a National Childhood Fund. Childhood inequality is a key issue India faces, and a package I would favor will be a universal, unconditional scheme that will provide family assistance to households with children. It will look something like this (let me know your thoughts): Pegged at 3% of India's GDP, and targeting about half a billion children of India, every child below 18 years of age will get an unconditional yearly cash transfer of ₹ 12000, remunerated monthly at ₹ 1000. As India's GDP rises (if very conservatively at 5%, when realistically we expect it to be @7-10%), then this income will rise too. Today, an yearly income of ₹ 12000, will be equal to ₹ 28900 in 18 years (@ 5%), and a total value of such saving (at 5% interest rate), will be about ₹ 5.2lack (₹ 2.16 lack NPV), that a child will be entitled to once they enter adulthood. A part of this income can be utilised by parents to fund unconditional expenses (which are expected to rise with a new child), but families will be nudged to freeze all the money for 18 years, and use this saving as a collateral for short duration interest free loans (short credit) if they so need. If they fail to return the money, then that amount will be deducted from this pool. There will also be a cap where parents with more than two children will be frozen off from utilising any money from their third child's account. So, families with two children, will get an yearly assistance of ₹ 24,000 (present day value). Hence, if I were a policy maker, a combination of instruments will be my preferred choice to ensure that an important demography of Indians (children), are better off in the future, and their family members are protected from risks. To this I will also add a comprehensive healthcare scheme about which I have written before. Government's Ayushman Bharat Yojana is an important milestone providing a significant health insurance (a key area of vulnerability) to India's 10 crore poorest households. As Guardian puts it "It's a godsend". To the Ayushman Bharat Yojana and my preferred model of subsystem-specific healthcare, I would also add a specialised healthcare program that provides unconditional healthcare coverage to all children. The money for such a scheme can partly come from the large savings pool that National Childhood Fund will create. |

Prateek RajPersonal blog. Views expressed are my own, expressed in personal capacity. Archives

May 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed