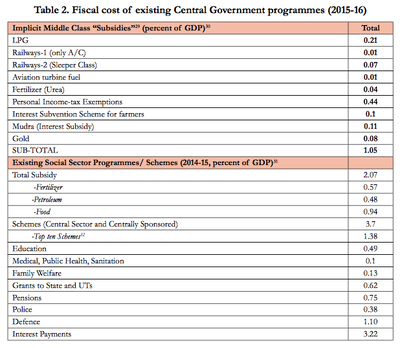

Source: Economic Survey of India 2017 Source: Economic Survey of India 2017 Basic income has been a topic of intense scruitny in India over the last few years. 2017 Economic Survey even wrote a report on Universal Basic Income (UBI) and its feasibility. Political parties across the spectrum have been toying with the idea. A minimum income guarantee scheme like NYAY (Nyuntam Aay Yojana) that has been proposed by Indian National Congress is a difficult to implement but a feasible scheme, contrary to the emerging narrative that its an impossible and unfeasible idea. Middle class in India gets 1% of GDP as yearly subsidies from GoI. Total subsidies by GoI amount to 2% of total GDP, and much of it is subsidy given on food. GoI's social sector schemes cost 3.7% of yearly GDP (not including the 2% subsides). A basic income scheme such as NYAY scheme which covers 20% of poorest households, will cost 2% of the yearly GDP. It is not at all in the impossible terrain. Funding a basic income scheme that costs 2% of the total GDP is especially feasible in an economy that grows at 6-8% each year. This implies that a fraction of gains that India makes each year go to the poorest Indians. The proposal that 20% of India's population should be guaranteed 2% of India's GDP is not a radical idea. Such a scheme is also inevitable, as cash transfers become easier, and it will not come to me as a surprise if BJP were also mulling over similar ideas (afterall the UBI report came under their government, and they proposed a minimal basic income for farmers). It is also important to consider that a basic income format of welfare was simply not feasible in a pre-IT era. A basic income based social welfare has become a possibility because of two key innovations that characterize India's development in 2010s: 1) development of a robust framework of universal identity (UID/Adhaar) system and online and mobile banking infrastructure, and 2) significant exapansion in bank access for people. However, NYAY is just one proposal. There are many alternative ways of distributing basic income. There are three questions that need to be considiered when discussing basic income as a policy:

Personally I am of the view that social welfare schemes should be as universal and unconditional as possible (although not always feasible), because implementing targeted and means-tested schemes open up a backdoor for inefficiency, bureaucracy and corruption. Bo Rothstein has a fantastic book on Quality of Government, which promotes the notion of impartial governance. So, I tend to favour basic income schemes that are universal and unconditional (hence a UBI), and at the same time do not completely substitute some in-kind welfare schemes like healthcare and education. I believe policies targeting the poor, should provide some income relief through cash transfers as a UBI, but other forms of in-kind relief (such as accessible healthcare, education, housing and amenities) cannot be replaced. Social welfare should still be seen as a basket of programs, which aid people in their incomes (yes), but also in their consumption. Note: If I designed a basic income scheme, it will target childhood inequality by developing a National Childhood Fund. Childhood inequality is a key issue India faces, and a package I would favor will be a universal, unconditional scheme that will provide family assistance to households with children. It will look something like this (let me know your thoughts): Pegged at 3% of India's GDP, and targeting about half a billion children of India, every child below 18 years of age will get an unconditional yearly cash transfer of ₹ 12000, remunerated monthly at ₹ 1000. As India's GDP rises (if very conservatively at 5%, when realistically we expect it to be @7-10%), then this income will rise too. Today, an yearly income of ₹ 12000, will be equal to ₹ 28900 in 18 years (@ 5%), and a total value of such saving (at 5% interest rate), will be about ₹ 5.2lack (₹ 2.16 lack NPV), that a child will be entitled to once they enter adulthood. A part of this income can be utilised by parents to fund unconditional expenses (which are expected to rise with a new child), but families will be nudged to freeze all the money for 18 years, and use this saving as a collateral for short duration interest free loans (short credit) if they so need. If they fail to return the money, then that amount will be deducted from this pool. There will also be a cap where parents with more than two children will be frozen off from utilising any money from their third child's account. So, families with two children, will get an yearly assistance of ₹ 24,000 (present day value). Hence, if I were a policy maker, a combination of instruments will be my preferred choice to ensure that an important demography of Indians (children), are better off in the future, and their family members are protected from risks. To this I will also add a comprehensive healthcare scheme about which I have written before. Government's Ayushman Bharat Yojana is an important milestone providing a significant health insurance (a key area of vulnerability) to India's 10 crore poorest households. As Guardian puts it "It's a godsend". To the Ayushman Bharat Yojana and my preferred model of subsystem-specific healthcare, I would also add a specialised healthcare program that provides unconditional healthcare coverage to all children. The money for such a scheme can partly come from the large savings pool that National Childhood Fund will create.

1 Comment

|

Prateek RajPersonal blog. Views expressed are my own, expressed in personal capacity. Archives

May 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed