Summary:

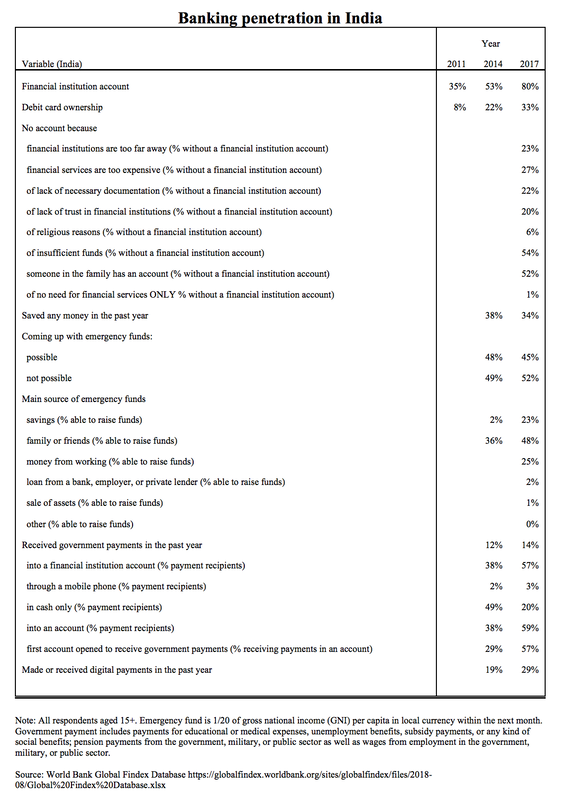

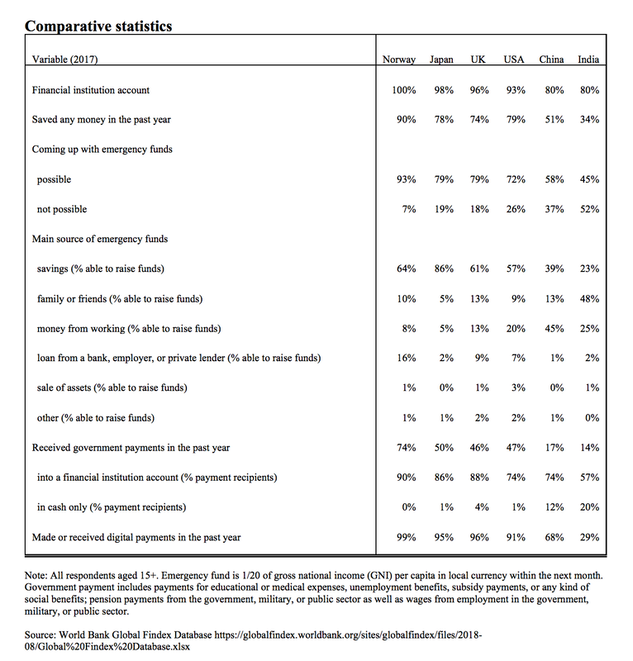

During a period of emergency, such as the coronavirus pandemic, the public needs immediate assistance. Governments need the necessary infrastructure of last mile and last person connectivity to provide such an assistance, and the universal access to bank accounts and digital payments can go a long way in making such immediate assistance possible. How is India placed on these parameters? The World Bank Global Findex Database can provide with some answers. The number of individuals with a bank account in a financial institution has significantly gone up in India in the 2010s (from 35% in 2011 to 80% in 2017) as per the World Bank Global Findex survey, with a larger fraction having debit cards (33%), and making/receiving digital payments (29%). Among those who still don’t have a bank account, the key reasons cited are a lack of sufficient funds (54%) and a family member already having a bank account (52%). Other factors leaving many unbanked are issues related to accessibility - financial services being too expensive (27%), too far away (23%), lack of necessary documentation (22%) and a lack of trust in financial institutions (20%). This creates a complication - the poorest and the most vulnerable are likely to not have sufficient funds and documents, and can find financial services to be too expensive. But at the same time they are also the ones who are in imminent need for bank accounts so that necessary public assistance and welfare support can reach them on time, especially during the period of emergency. During the times of emergency, more than half of the respondents in India said that they were not able to raise emergency funds within a month (52%). For those who were able to raise emergency funds (45%), the chief source of such funds was family or friends (48%), followed by money from working (25%) and savings (23%). Compared to developed countries like Norway, Japan, UK and the USA, an alarmingly larger number of respondents are unable to raise emergency funds in India, and are dependent on family or friends for support. Government payments can become a salient form of funding for Indians in times of emergency, and can be an important policy goal especially given that the majority of Indians are unable to unable to raise any such funds. Government payments of social benefits has not significantly increased (14%) over time in India, but the mode of these payments has become more cashless (cash payments are down from 49% in 2014 to 20% in 2017), with a large fraction of such payments reaching the beneficiaries directly in their accounts (59%). Among those accounts that receive government payments, a large fraction were opened for the first time to receive government payments (57%). Compared to other developed countries government payments still reach a small fraction of Indians (14%). While there is a thrust on digital penetration and cashless payments in India, very few Indians do digital payments (29%). In developed countries, digital payments are ubiquitous (>90%) and government payments in hard-cash are minimal (<5%). In conclusion, based on the data it appears that India has significantly improved its capabilities in banking and digital penetration. Yet the most vulnerable are still to be reached. Especially, the most important fact that policy makers should address is this: a majority of Indian respondents in the survey say that it is not possible for them to raise emergency funds within a month's time, and if they can then they rely primarily on their social networks - family and friends. In times of a crisis like the coronavirus pandemic, such a precarious support system leaves the most vulnerable at risk. With government payments reaching a meagre 14% of the population in India, there is a lot of scope for improvement so that every Indian can be reached out and helped in times of crisis. (update) As the Economist points out in its latest edition (4th April 2020), India's outlay to the coronavirus pandemic is a paltry 0.8% of the GDP ($23 billion), when other countries are spending much higher. The social welfare infrastructure is today ready in India; now is the time for making the last mile and last person connections, so that most vulnerable Indians can be reached. Indians await a new deal, and we should come together as policy makers to provide it now.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Prateek RajPersonal blog. Views expressed are my own, expressed in personal capacity. Archives

May 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed