|

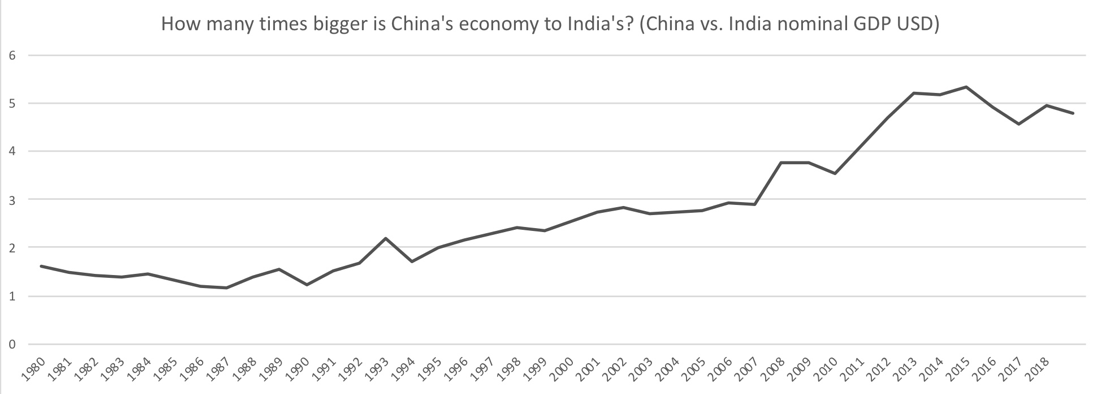

The Chinese economy ($13.4 trillion) is 5 times larger than India’s ($2.7 trillion) even though the countries are similarly sized in population. A small fraction of China’s large GDP can fund multiple Indian military budgets, and with large budgets, China is rapidly expanding its military capabilities.

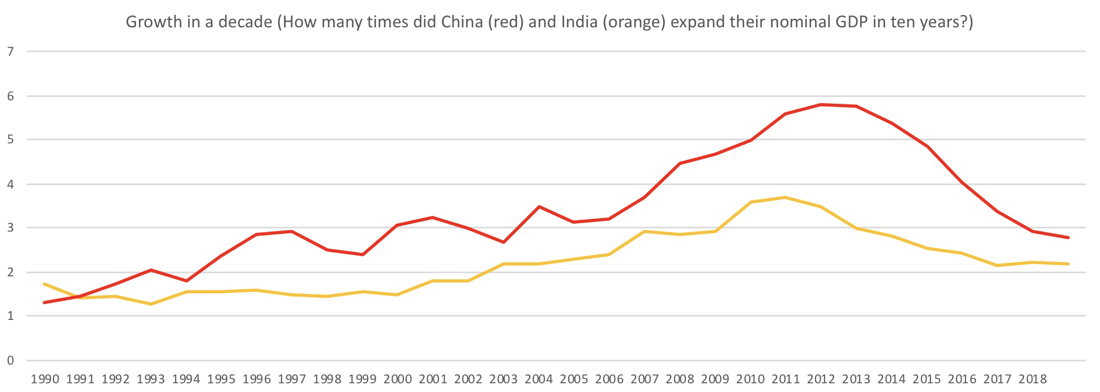

India will become the fifth largest economy in the world this year. While that is reassuring, at no point in history of modern India has India been so weak relative to its neighbor in economic size. Even though India is growing at a rapid pace it is not growing fast enough. In the 2000s India expanded its nominal GDP more than three times. It should have expanded this decade even more, but this was a lost decade and in 2010s India’s GDP only doubled. During the same period China expanded its GDP by about six times in the 2000s, while in this decade it still managed to expand its GDP by about thrice. Given the urgency of the situation, it is important that politicians prioritize economic issues over jingoism and cultural politics. Here’s the bottom line- patriotic slogans cannot fund India’s military. Only a growing economy can.

1 Comment

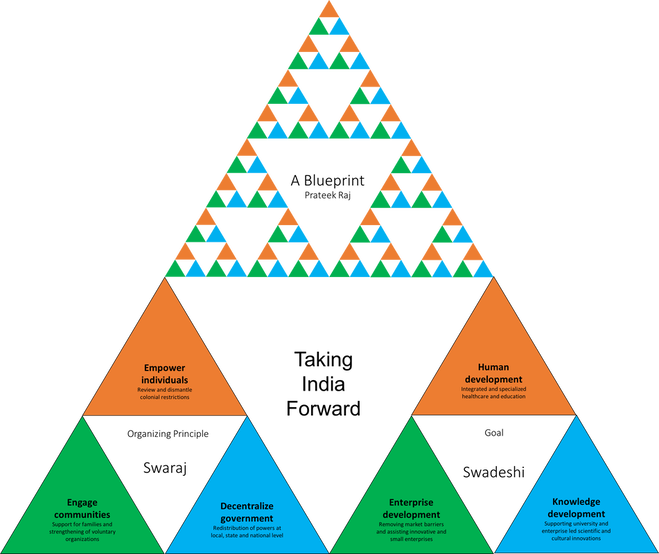

India has seen transformational change over the last three decades. Such a transformation has turned India into a highly aspirational country. Today the country wants better jobs, better health care, better public infrastructure and quality of life, better governed cities and modernization of agriculture and rural economy (see 2018 ADR voter survey). To achieve these aspirations India needs to empower its communities and turn them into producers of high-value goods and services. Moving up the value chain The first priority of Indians today is to enjoy better employment opportunities. This requires Indians to quickly move up the value chain, so that their skills and services can have greater demand in the labor market. China has been successfully making such a transformation. Consider the case of Indian IT firms like TCS and Infosys that were once supposed to turn India into an IT superpower. Today they have become stunted giants, while Chinese firms have built competitive global brands (Huawei, Tencent) in the same technology industry. While China has assertively moved from low cost manufacturing to production of high end goods and services, India has not. Indian IT "giants" still continue to do backoffice tasks, and are not providers of high end goods and services like Microsoft. The rural economy needs to move up the value chain as well, and we need more processing done at the rural level so that they do not lose the surplus of their produce to intermediaries. India needs Indian products to turn into global brands, not intermediary inputs to production of other companies. At the same time, for certain regions like North India, we need specific interventions to promote urban development as it suffers from a metropolitan vaccum. Why is India not moving up the value chain? Moving up the value chain requires rapid improvement in skill set of Indian people. For example, Indian healthcare needs about 2.7 million doctors (three times the current number) to satisfy India’s healthcare needs, which requires a radical new scale at which Indian education system needs to function. The current system of university degree based education although necessary (e.g for training doctors), has become inadequate for the needs of India’s large young population. Today with help of ICT, learning can be commodified, and people can learn specific skills in shorter duration, and upgrade their capability. We need an education system that encourages “constant learning” and we need to reimagine universities not as ivory towers in gated communities, but as open public spaces where citizens can walk in and learn. We need to also link high schools and diploma institutes to regional industries where students are taught necessary skills and do not wait for employment until they are in their mid 20s. For the future of India, the role of ITI type vocational institutions is crucial. If India wants IITs to matter too, then it needs to rapidly expand its research budget. For Rs 3000 crore (at cost of a mega statue), as many as 400 high end science labs with seed grant of a million dollars can be established. Strengthening the community The above ideas aren’t radical. Most Indians aspire for common sense investments: better infrastructure, governance and quality of life. Yet, simple demands do not get delivered. Why? It is important to note that a nation of 1.35 billion cannot be governed from New Delhi. The average size of an Indian province is 45 million which is larger than most European nations. Central governments and Lutyens mandarins can keep proposing policies after policies, yet such top down policies are bound to fail in a country of the size and scale as India. Consider a community of size of an Indian village with a population of around 1350 people each, then each of these 10 lack communities, need to get greater devolved powers. India needs effective and local community governance, which has four characteristics: 1. Citizen accountability, and open democracy where each household is member of the governing council. 2. The council has the power to raise funds and taxes, and to enact regulations. 3. Executive accountability of local mayors who are responsible for their village or neighborhood affairs. 4. Establishment of an independent local press, and a public square, with library (museum), community center etc as community amenities Of the 25 lack crore rupees the central government collects as taxes annually (which should rise with greater growth and formalisation of the economy), it should return a significant fraction (about 20% of the budget), directly to the local communities. If 20% of central funds were distributed among the 10 lack communities of 1350 people (less than 300 households) each, then each community would get a grant of around Rs 50 lack annually as a corpus to fund public goods within the community, over which a governing council will have full budgetary power. One can envision a kind of tax democracy, where each household gets a size weighted fraction of this Rs 50 lack community grant (about Rs 18500 each) and it can decide which public projects they will contribute their portion of funds to. The choice of public projects can be proposed by a mayor and its executive cabinet, and the governance council made of all village households can vote which public project gets how much funds, or else if the fund gets invested in a community savings account. Such a community grant can go a long way in establishing a baseline of services and quality of life, that each Indian deserves, fostering open democracy and provide real significant but constrained devolved powers to local governments. Empowering communities was a promise of independence (Swaraj) that is left undelivered, and when communities are empowered to invest in themselves, what shall they invest in? In their future. They shall invest in resources that make them compete better in the increasingly connected and globalized world. PS: The figure below digramatically represents the ideas of Swadeshi and Swaraj and its various components, which I elaborate in the caption and the link here.  First set of measures (Swadeshi) are fundamental, which help citizens succeed, and are well acknowledged: Without an educated and healthy population base, economic success cannot be broad. Thus the focus on Human Development. Similarly, without a strong economic engine that supports free enterprise and flow of capital/resources, an educated and healthy population cannot be sustained. Thus the focus on Enterprise Development. At the core of a strong economic engine lies the ability of a nation to generate enough innovation, that it can create value in a competitive global economy. Thus the focus on Knowledge Development. However, while these development measures are fundamental, achieving them is dependant on the specific regional characteristics. Hence, Swaraj. We have to empower individuals and free them from social restrictions that bind their abilities. Colonial laws and social mores that restrict the pursuit of happiness of women and sexual minorities need to go. The same way, we have to take the government away, and bring back the focus on communities. Mahatma Gandhi and APJ Kalam both dreamt of autonomous village republics. India had a proud history of Janpadas. These republics were built around voluntary and engaged communities. These engaged communities need to be empowered in the government, through decentralised governance. What is not necessarily the purview of the centre and the state, should be local. There should be stronger mayors and empowered panchayats, that are publicly accountable. Reign of tradition

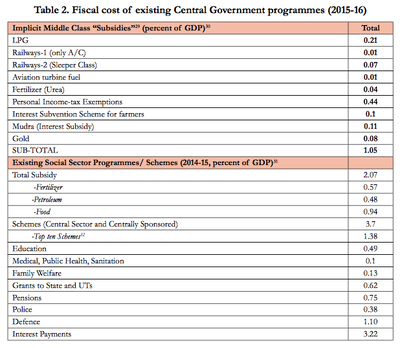

A traditional society revers the wisdom of the ancestors. In the earliest period of human history, the pace of growth was slow, and traditions- or received wisdom from ancestors - were good pointers on how one should behave. Not all traditions were fair. Some like the caste of system or feudalism were atrocious. But in an era where change was slow, these traditions (good or bad) were persistent. It was difficult to mount a revolution. That is why, we do not hear about revolutions in the ancient past that very much. We hear about the American or French Revolutions in the eighteenth century, or about the Indian independence movement since the nineteenth century, or if stretching to the sixteenth century, we hear about the Protestant Reformation. Why did revolutions against established traditions become common in the early modern era? It was difficult to coordinate hundreds of thousands of people together to mount a mass rebellion against a dominant group. So, technologies such as the printing press, that emerged in the fifteenth century, became important coordinating technologies, as they could print pamphlets and books for call to action. So, traditional society began to lose its grip only once technological and economic progress began. As lives of people transformed within generations, traditions that were passed down from one generation to the next were no longer good guides of behavior. What replaced tradition in this era of rapid change? It was rationality. Rise of Rationality While Asian civilizations were at the helm of progress for much of the human history, Europe began to catch up in the modern age. Economic historian Joel Mokyr says that the key difference between early modern Europe and elsewhere was the lack of reverence to ancestors. As Europeans travelled in the age of exploration, and read ancient books, they discovered the gaps in knowledge of their ancestors. They began to question ancestral wisdom, and began believing that their generations may very well be smarter and wiser than the past. When such a break from tradition took place, something needed to replace the guidance of tradition? In place of tradition people began to think for themselves, individually, and began relying on their rational faculty. The ancient world had no dearth of rational thinkers. In Hindu traditions two of the six schools- Nyaya and Vaisheshika rely heavily on logic to learn about reality. But in traditional societies, such logical schools faced tough competition from schools that relied on rituals and traditions, where testimony was highly valued. In the modern age, testimony from ancient texts and ancestors is given much less credibility than testimony of the peers, and inferences of one’s own mind. Such a system that emphasizes peer and rational learning inevitably gave rise to the scientific method. It should not come as a surprise that rise of rationality gave rise to an Age of Enlightenment and science in the seventeenth century. Stalwarts like Newton and Darwin revolutionized human understanding of the world around us. But with such “enlightenment” and rationality came dark realities. As Europeans, became more technologically advanced, they left a trail of exploitation around the world. India faced several famines during the colonial misrule. Unchecked power of European technological superiority was especially devastating for ordinary Europeans themselves as they fought two cataclysmic world wars. Nazis, fueled by pseudoscientific ideas of a Darwinian race war, perpetrated unspeakable atrocities including the Holocaust that systematically killed millions of Jews. So, age of rationality, despite its ability to bring rapid technological and economy progress, reached a nauseating conclusion during the World War 2, characterized by devastation, genocide and moral bankruptcy at a scale unheard of in human history. How could rationality culminate in such a devastating end? Because it was devoid of morality and empathy, and especially devoid of a concern for human dignity. Primacy of Dignity Consider the founder of modern statistics - Francis Galton. He was a polymathic genius who gave the world regression and fingerprints. But he was also the founder of eugenics, and believed human races were inherently different, and like breeds of animals, each race had unique characteristics that were hard baked by nature. Eugenics, an idea that was further popularized by the Nazis, believed in designing a better race using scientific principles, where the ideal race was the Nordic-Aryan ideal. In name of such improvement of racial stock, “impure” and “inferior” groups like the Jews, or “defective” people like those who were disabled or belonged to the LGBT community, were killed in gas chambers in a highly bureaucratic and organized operation. While the Nazi obsession with a purity may seem like a perversion, but such ideas of group superiority were not exclusive to the age of rationality. Traditional societies were far from egalitarian. Gender, religious or caste discrimination was rampant is such societies for long, with fetishized notions of purity and pollution playing an important role in regulating conduct. Twentieth century saw rapid expansion in human rights. The second world war could not have been won, without the contribution of armies made of people of color, and of factories run by women. After the end of Second World War, there was a greater reflection on the perils of Nazism type ideologies that failed to acknowledge human dignity. In the 20th century, women sufferage movement, civil rights, Dalit, LGBT and the several independence movements, most prominently in India, brought representation to the marginalized groups. As their voices were heard more, reason in itself was no longer an appropriate guide for decision making. It had to be coupled with the notion of dignity. For example, John Rawls in his pathbreaking book on Justice, provided a framework that combined reason with dignity. He said, we should design a society keeping a veil of ignorance about where we as individuals would be positioned in such a society. If this principle of veil of ignorance gets applied, it is difficult to advocate for lesser rights for marginalized groups, and rights and laws become more inclusive and universal. Consider the notion of “men” in the American constitution, which has evolved from including only land owning white men in eighteenth century, to all humans in the twenty first. Conclusion In a traditional society, all people had a “proper” place. Consider the position of transgenders in Indian society. While being a transgender was tolerated in Indian society, and at times transgenders were even worshiped, but the social and economic roles they could take were severely limited. As societies became more rational, it did not spontaneously create an inclusive society. Labeling of “proper” and “improper” humans became common. For example in Victorian England, the rights of LGBT persons were severly curtailed, and anti-LGBT laws and sentiments diffused in other colonies. However, in the modern era human dignity is more important than reason or tradition, and in this era we need to empathize, stand in other people’s shoes and question if it is the job of society to dictate what is the “proper” thing for people to do. This tradition of empathy, and primacy to dignity, gives a simple solution: we must design a society which gives all people the freedom to decide what is proper for them. If a person’s life decisions do not directly affect our own, should we decide on their behalf what is “proper” for them? Similarly, when people’s individual decisions affect others, should some stakeholders take decisions for the rest? A fully realized society, that gives primacy to dignity, and tests both rationality and tradition on that anvil, naturally offers universal fundamental rights to all people, and develops participative and democratic systems of collective decision making. The ideals of such a society are codified in great constitutional texts such as the the American and Indian constitution. Though these constitutions codify great and noble ideas and are great achievements of mankind, the application of these ideas nonetheless depends on those who practice and apply them in their daily lives. Do we give primacy to human dignity, and test our traditions and rationality on that anvil? Or are we comfortable in defending our traditions or reasoning even when they violate the dignity of fellow human beings? The answers to the questions above will eventually decide the fate of our society in the long run.  Source: Economic Survey of India 2017 Source: Economic Survey of India 2017 Basic income has been a topic of intense scruitny in India over the last few years. 2017 Economic Survey even wrote a report on Universal Basic Income (UBI) and its feasibility. Political parties across the spectrum have been toying with the idea. A minimum income guarantee scheme like NYAY (Nyuntam Aay Yojana) that has been proposed by Indian National Congress is a difficult to implement but a feasible scheme, contrary to the emerging narrative that its an impossible and unfeasible idea. Middle class in India gets 1% of GDP as yearly subsidies from GoI. Total subsidies by GoI amount to 2% of total GDP, and much of it is subsidy given on food. GoI's social sector schemes cost 3.7% of yearly GDP (not including the 2% subsides). A basic income scheme such as NYAY scheme which covers 20% of poorest households, will cost 2% of the yearly GDP. It is not at all in the impossible terrain. Funding a basic income scheme that costs 2% of the total GDP is especially feasible in an economy that grows at 6-8% each year. This implies that a fraction of gains that India makes each year go to the poorest Indians. The proposal that 20% of India's population should be guaranteed 2% of India's GDP is not a radical idea. Such a scheme is also inevitable, as cash transfers become easier, and it will not come to me as a surprise if BJP were also mulling over similar ideas (afterall the UBI report came under their government, and they proposed a minimal basic income for farmers). It is also important to consider that a basic income format of welfare was simply not feasible in a pre-IT era. A basic income based social welfare has become a possibility because of two key innovations that characterize India's development in 2010s: 1) development of a robust framework of universal identity (UID/Adhaar) system and online and mobile banking infrastructure, and 2) significant exapansion in bank access for people. However, NYAY is just one proposal. There are many alternative ways of distributing basic income. There are three questions that need to be considiered when discussing basic income as a policy:

Personally I am of the view that social welfare schemes should be as universal and unconditional as possible (although not always feasible), because implementing targeted and means-tested schemes open up a backdoor for inefficiency, bureaucracy and corruption. Bo Rothstein has a fantastic book on Quality of Government, which promotes the notion of impartial governance. So, I tend to favour basic income schemes that are universal and unconditional (hence a UBI), and at the same time do not completely substitute some in-kind welfare schemes like healthcare and education. I believe policies targeting the poor, should provide some income relief through cash transfers as a UBI, but other forms of in-kind relief (such as accessible healthcare, education, housing and amenities) cannot be replaced. Social welfare should still be seen as a basket of programs, which aid people in their incomes (yes), but also in their consumption. Note: If I designed a basic income scheme, it will target childhood inequality by developing a National Childhood Fund. Childhood inequality is a key issue India faces, and a package I would favor will be a universal, unconditional scheme that will provide family assistance to households with children. It will look something like this (let me know your thoughts): Pegged at 3% of India's GDP, and targeting about half a billion children of India, every child below 18 years of age will get an unconditional yearly cash transfer of ₹ 12000, remunerated monthly at ₹ 1000. As India's GDP rises (if very conservatively at 5%, when realistically we expect it to be @7-10%), then this income will rise too. Today, an yearly income of ₹ 12000, will be equal to ₹ 28900 in 18 years (@ 5%), and a total value of such saving (at 5% interest rate), will be about ₹ 5.2lack (₹ 2.16 lack NPV), that a child will be entitled to once they enter adulthood. A part of this income can be utilised by parents to fund unconditional expenses (which are expected to rise with a new child), but families will be nudged to freeze all the money for 18 years, and use this saving as a collateral for short duration interest free loans (short credit) if they so need. If they fail to return the money, then that amount will be deducted from this pool. There will also be a cap where parents with more than two children will be frozen off from utilising any money from their third child's account. So, families with two children, will get an yearly assistance of ₹ 24,000 (present day value). Hence, if I were a policy maker, a combination of instruments will be my preferred choice to ensure that an important demography of Indians (children), are better off in the future, and their family members are protected from risks. To this I will also add a comprehensive healthcare scheme about which I have written before. Government's Ayushman Bharat Yojana is an important milestone providing a significant health insurance (a key area of vulnerability) to India's 10 crore poorest households. As Guardian puts it "It's a godsend". To the Ayushman Bharat Yojana and my preferred model of subsystem-specific healthcare, I would also add a specialised healthcare program that provides unconditional healthcare coverage to all children. The money for such a scheme can partly come from the large savings pool that National Childhood Fund will create. In the three lectures held on 22nd, 26th and 29th October, 2018 in the memory of Prof. Dwijendra Tripathi, we studied the broad historical evolution of businesses and markets. It was a story of expansion of the social circle. We discussed the macro-level implications of who are our friends and what is the nature of networks we make.

In the first lecture we learnt about the two types of exchange: one which is embedded in networks and hierarchies, and another that can rely on arm’s length interactions with strangers. We discussed how embedded systems of exchange like merchant guilds can persist due to a lack of incentives or information, or because of salience of identity in embedded exchanges. In the second lecture we looked at the factors that can widen the social circle and give rise to impersonal and cosmopolitan social systems. We learnt that strong institutions, a trustworthy culture or “laissez-faire” markets alone can not be the recipe for the emergence of impersonal exchange as each of them are prone to corruption, decay and opportunism. We discussed the importance of incentives and formalization in impersonal exchange, and how trade and information shocks can play an important role in triggering a co-evolution between generalized institutions, standardized business norms, and impersonal exchange. We discussed how this process panned out in Northwestern Europe, and how the same processes may lead to growth in India, as long as the growth remained inclusive. In the third lecture, we discussed the forces that drive such evolution. First we looked at the role of institutions on development, and specifically looked at formal, legal and local ethnic institutions. Next, we discussed the cultural ingredients that make functioning markets, and discussed the importance of historical persistence and trust, and how "market for ideas" influenced culture and institutions. Next, we discussed how technology influences the market, and discussed the importance of information and transport technology, and the media. Humans need communities. After all, we are social beings. These communities should be built around our neighbors, co-workers, family members, and friends. But, there should be a scope for inclusion of new people - of strangers - in our communities. Without inclusivity, diversity, and trust, communities become stale, fragmented and suffocating for individual growth and freedom.

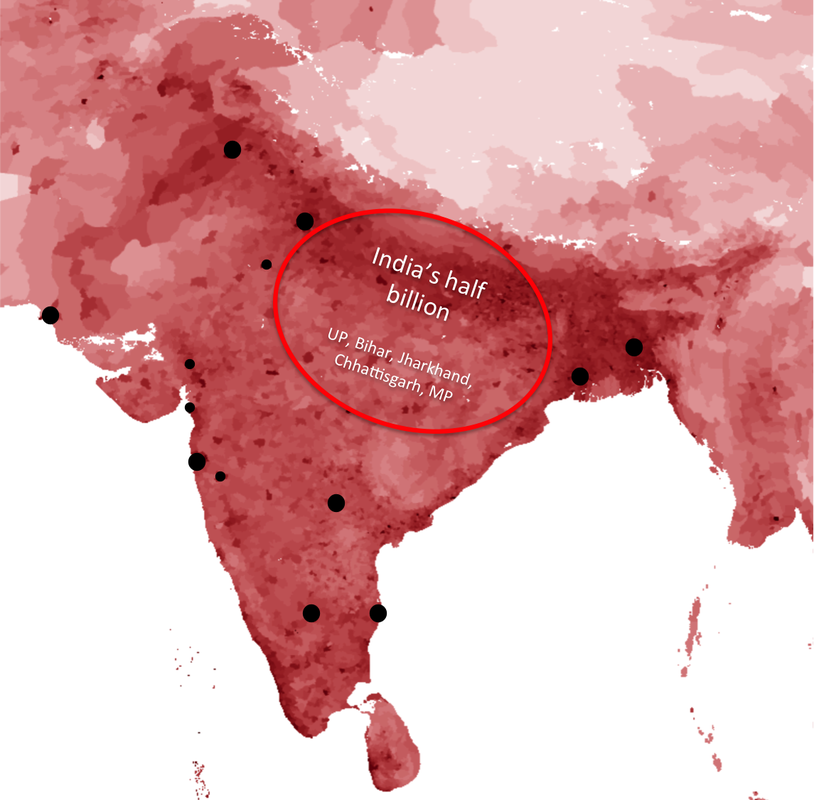

People often have a very idealized vision of communities. They think that communities are places of high social capital. Yes, they are, but what kind of social capital? Actual communities (throughout the world) can often look like an Indian village fragmented and stratified by the "caste system," where people adhere to vigorously enforced community norms and are skeptical of outsiders. After the sixteenth century, "communities" like merchant guilds began to diffuse, and give way for market-based societies in Europe. And so was laid the foundation of the modern, more bourgeois, and more cosmopolitan world. But, in India the caste identity became more salient during the colonial period, which hinders India's rise today as a prosperous and modern society. Hopefully, India is undergoing a bourgeois revolution at this moment. Will all parts of India benefit from this revolution equally? (Here's a longer Thesis Introduction) The Hindi speaking provinces of India: Uttar Pradesh (UP), Bihar, Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh and Madhya Pradesh (MP) together make a population close to half a billion [1]. Historically, this region was home to important cosmopolitan cities of the world, like Kashi and Patliputra. Just over a hundred years ago, four of the ten largest cities (Lucknow, Banares, Kanpur and Agra), and eight of the twenty largest cities in India (+ Allahabad, Patna, Bareilly and Meerut) were in the region (1911 census). But today, the region suffers from a “metropolis vacuum”, because it has no major metropolitan agglomeration to attract talent and investments.

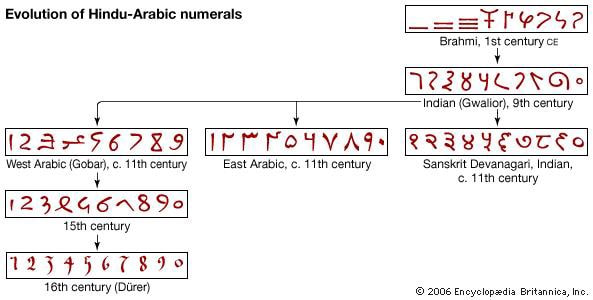

The six largest cities of India, Delhi, Mumbai, Kolkata, Chennai, Bangalore, and Hyderabad all lie outside of this Hindi heartland. The other new upcoming urban centers like Pune, Ahmedabad, and Surat also lie outside of the region. Among the ten largest cities none are in the region, while only five cities (Lucknow, Kanpur, Indore, Bhopal and Patna) belong in the top twenty (2011 census). The glaring absence of a major metropolitan center in the region has forced young people to migrate away from the small towns and move to other cities in the West and the South. Today, India needs sustained double digit economic growth (Financial Times, 2015), to fulfill the aspirations of its highly ambitious and very young population. During the previous decades, India’s growth was primarily centered in its West and the South. But, if today India aims to sustain and accelerate its progress, the Hindi heartland needs to become an engine of growth too. Can such growth happen in the absence of a metropolitan anchor? Cities play an indispensable role in any region’s economy. If we consider the historical rise of Europe, cities like Amsterdam and London played an indispensable role in its progress. At the end of the fifteenth century, Northwestern Europe was not very different from parts of India or China. Yet the region leap-frogged ahead of the historically dominant economies of Asia, as Northwestern Europe underwent a “bourgeois” revolution (McCloskey 2016) in the sixteenth century. In this region, cities such as Amsterdam, Hamburg and London at the Atlantic coast, established rules-based-markets (Ogilvie 2011), and they attracted trade, talent and capital. This agglomeration helped in the development of a bourgeois city dwelling class that saw investment in learning and enterprise (and not land and nobility) as the path to progress. Eventually, the Northwestern European region developed a distinct culture of growth (Mokyr 2016), as innovation became more frequent (either through invention or imitation) and profit making became more desirable. As rulers found new ways to generate revenue, they facilitated the formation of joint-stock-companies like the English East India Company, which traded overseas, and eventually this process of innovation and commerce (often along with colonization) culminated in the Industrial Revolution, which first was sparked in eighteenth century England. Nobel laureate Robert Lucas (2018) in his recent research has emphasized the importance of cities in the industrial revolution. Cities match capital with talent. Cities that are accessible (not controlled by a clique of business and political elites) and cosmopolitan (not hostile to particular groups of people) attract capital and bring people of diverse backgrounds and talents together to form productive partnerships. Such cities motivate people from nearby areas to learn new skills and to invest more in the education and health of their children. In India, we can see this historical process of growth happening in real time, with the meteoric rise of Bangalore. In 1911 Bangalore was only a minor city in India. Today it ranks third, thanks to an environment that is welcoming to entrepreneurs, innovators and investors. What happens in regions like the Hindi heartland, which lack major cosmopolitan cities? In such regions capital and talent are matched much less efficiently. If people do not expect that their talent will be rewarded because of this mismatch, they have lower interest in investing in themselves and their children. The mismatch creates a vicious circle of low human capital and low growth. Such vicious circle where people don’t have hope for a better future, creates a fervent ground for anti-social behavior, like lynching and vigilantism. The Hindi heartland needs a few major cities, to get out of this vicious circle. When discussing Indian economic growth, much emphasis is given to India’s central government. India’s central government plays a very important role in pushing for the much-needed reforms, which can make the match between capital and talent more efficient. But India’s state governments and even more locally – the mayors and their municipal councils are key players in shaping the direction of India’s regional development. If India’s Hindi heartland is to grow, it needs state governments and municipal councils that appreciate the importance of large and cosmopolitan cities in economic growth. India’s central polity, both on the left and the right, understands the importance of cities in economic development. But is it concerned about the metropolis vacuum that is diminishing the prospects of India’s Hindi heartland? Recently, India has made plans to develop industrial corridors connecting its major cities. The Delhi Mumbai Industrial Corridor (DMIC) has received much attention in the media, which connects the two cities via western cities like Jaipur, Ahmedabad, and Surat. Such projects offer much potential for future economic growth. Yet, if Indian policymakers are serious about ending the metropolis vacuum faced by its half a billion citizens, they should take concrete and targeted steps to accelerate urban development in the region. The Amritsar-Kolkata industrial corridor is a useful step, and more projects focused specifically on the heartland are needed to remedy this metropolis vacuum. The good thing about urban growth is – cities grow by themselves – as long as the local governments “facilitate” adequate urban public goods (like roads, water, electricity and public transport) and establish a rule of law, which develops a favourable environment for all enterprises, not a chosen few (i.e. they are pro-market not pro-business, see Rajan and Zingales, 2004). Partly, the stagnation of cities in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar is because of the absence of an unbiased rule of law, which should be blind to a person’s party, ideology, religion, caste or class. Which entrepreneur will like to settle in a city, where the government’s attitude towards you and your business can change as quickly as the climate? It is also important to fix accountability and urban governance by empowering local mayors. Indian cities suffer from severe handicaps due to poor urban governance (Janagraha ASICS 2017). Cities around the world, from London to Chicago have influential mayors, and residents hold them responsible if the city fails to function well. When heavy rains clog cities like Patna, who is to be held accountable? The government of Bihar which represents ten crores (hundred million) people, or a local mayor? The answer to this question should be clear, so that we can stop passing the buck. Targeted steps to rejuvenate cities of Hindi heartland are a win-win for all stakeholders in India’s growth. If metropolitan cities can emerge in the region, it will relieve the migratory pressures many growing cities like Bangalore are facing today. Here is the bottom-line: Of the 1.35 billion people of India, about half a billion cannot be left behind. An urban policy that emphasizes healthy growth of cosmopolitan cities throughout India including its Hindi heartland is a crucial ingredient for achieving sustained two-digit GDP growth, which India acutely needs. [1] 475 million in 2018. (220 mm in UP, 110 mm in Bihar, 80 mm in MP, 35 mm Jharkhand, 30 mm Chattisgarh) Financial Times 20: https://www.ft.com/content/a44b8f48-be61-11e4-a341-00144feab7de McCloskey, Deirdre N. Bourgeois equality: How ideas, not capital or institutions, enriched the world. Vol. 3. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016. Ogilvie, Sheilagh. Institutions and European trade: Merchant guilds, 1000–1800. Cambridge University Press, 2011. Mokyr, Joel. A culture of growth: the origins of the modern economy. Princeton University Press, 2016. Lucas Jr, Robert E. "What Was the Industrial Revolution?." Journal of Human Capital 12, no. 2 (2018): 182-203. Rajan, Raghuram G., and Luigi Zingales. Saving capitalism from the capitalists: Unleashing the power of financial markets to create wealth and spread opportunity. Princeton University Press, 2004. Janagraha ASICS 2017: http://janaagraha.org/asics/ASICS-2017.html One of most fascinating pieces of global history is this: The modern number system was introduced in Europe by an Italian merchant named Leonardo of Pisa (whom we today call Fibonacci) in the beginning of 1200s. Leonardo learnt the decimal system when he visited Béjaïa in Algeria. He was taught the number system by Muslim merchants, who themselves popularized the decimal system after learning it from Hindu merchants. The first mention of zero has been found in Indian commercial text from 200–400 AD written in Sharada script discovered in Bakhshali, Pakistan (today preserved in Oxford’s Bodlean Library).

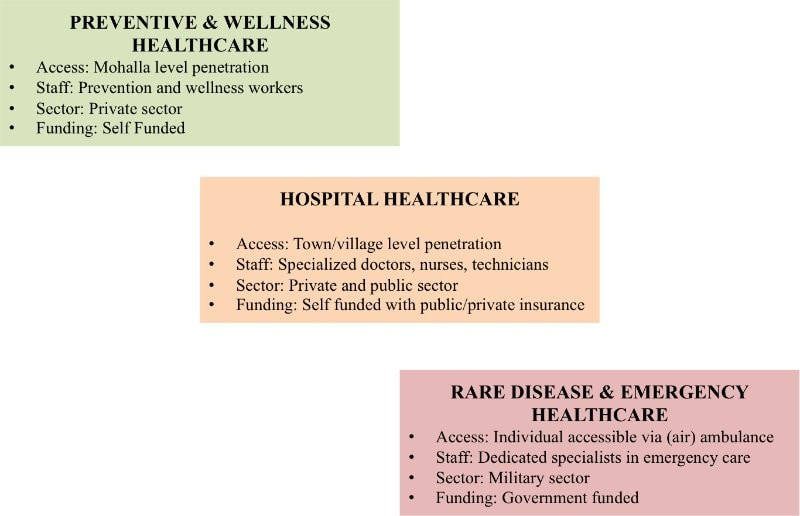

For about 250 years after Leonardo, his number system wasn’t well known to most Europeans. Much of Europe until around 1500s used the Roman numbers. Imagine performing division using Roman numbers! It was in 1450s after an inventive German blacksmith named Gutenberg invented the movable type Printing Press in Mainz, that the Hindu-Arabic number system began replacing Roman numerals, and revolutionized mathematics, science and commerce! We can improve India's healthcare, by fulfilling the specific requirements in logistics, access, staff and funding of three distinct subsystems in healthcare: 1) preventive & wellness, 2) hospital and 3) rare disease & emergency.

Last month we fundraised for a 9-year old boy named Suman who was suffering from Japanese encephalitis, and whose father was unable to afford treatment. Suman's situation and of several others (visit Milaap) revealed the glaring flaws in the Indian healthcare system. What kind of independence is it, when the masses can't afford a treatment that the family and friends of the more affluent, powerful and connected can? We have to stop looking at Healthcare as one large system, and view it as a collection of several subsystems:

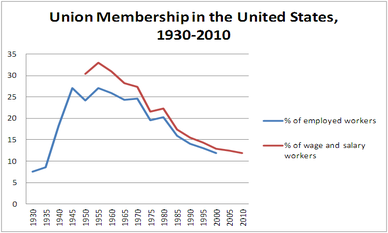

Preventive & wellness healthcare needs to be accessible in close proximity to everyone. The costs of this care are low, and closely linked to nutrition and lifestyle, and the costs can be borne by people themselves. There is a huge scope for the private sector in this area and the government should promote private enterprise in the preventive & wellness healthcare sector. Special emphasis should be given to women's healthcare needs, as the prenatal womb environment can have a significant impact on the future health of children. Hospital healthcare needs doctors, nurses and advanced equipment, and it serves at one time a smaller number of people in need for medical care. The costs are high, but the middle class and richer families can pay for the treatment, while the poor should be assisted in part by the government. There is a scope for both private and public institutions in hospital care. Managing and improving hospital care has been the emphasis of governments, but without proper preventive & wellness and rare disease & emergency healthcare systems, hospital healthcare is overloaded and inefficient. Rare disease & emergency healthcare needs specialised and sophisticated care. The number of people served by the system is significantly lower, and the costs of care are very high, especially when they require a rapid response (air ambulance) or rare surgery (transplants). The cost of this care can be borne by the government for all cases. The government should institute a military style health service (MediCorps?) that caters to special needs of rare and emergency healthcare. By classifying healthcare in preventive & wellness, hospital and rare disease & emergency, and by having special logistics and funding arrangements for each, we can improve the healthcare system. When preventive & wellness care is good, the need for hospital care is lower, and this saves costs for everyone. Similarly, the treatment of rare disease & emergency conditions should work like a national insurance scheme where people by making small investments, insure themselves to get military grade well-coordinated health service. Any more suggestions, especially from people associated with healthcare, are most welcome.  I do not like to act like a seer, as we often get caught up in bubbles, believing the immediate past trends will carry forward in the future. The number of uncertainties in the world are too many, to predict anything with either precision or accuracy. Anyway, if a pattern emerges that lasts a decade, you need to give it some due emphasis. Many say the rising inequality is a problem. I agree it is, but I would say the rising inequality, in the long run, is a greater problem for the rich than the poor because it is the rich who will be the greatest losers. The financial crisis of 2008 was an unprecedented event, but the events that followed were more unprecedented. Those who were the direct actors in the creation of the storm, the finance industry, has withered the storm and even taken huge bonuses and public bailouts home, while those who were at the receiving end still struggle to get over the damaging consequences of the great recession. I will not argue the merits of either side but will provide a clinical analysis of what such an uneven growth implies - where the rich got richer and the poor struggled. We can see what it implies all around us, the Occupy Wall Street, the 2014 Ferguson Protest, all of it are fuelled by a perceived sense of injustice, that few wealthy men (mostly) have an unnaturally large level of control on people's lives. I have heard the lobbyists of the Wall Street and the City argue how such perceptions are misjudged. However, you can't change perceptions by giving fat bonuses to bosses! Even if for a moment it is agreed that the agitated public today is merely a victim of misperception, the misperception is too strong. Maybe there exists a belief in the power circles of the Western world that such sense of injustice will calm down once some fraction of the large wealth of rich will trickle down. Some believe that we should let the 'hard working and smart' rich get very rich and then some parts of their income will eventually go to feed the 'lousy' poor. What explains this patience of the disproportionately rich with the current agitations? In the past few decades, the social capital in western democracies has eroded. Prof. Robert Putnam in his book Bowling Alone presents this case, where he argues how the famed civic values of America are under threat. The union membership has declined precipitously in the USA in the past decades. I have my own analysis of why this is happening. I agree with Prof. Noam Chomsky that today media in the developed world closely resembles an oligopoly or even a cabal owned by a few well-connected firms. Although a paper by Mullainathan and Shleifer "The Market for News" at AER (2005), suggests the news media is driven primarily by the slant of its customers, and not producers, however, there also exists evidence how media can impact people's perceptions (see Chiang, Chun-Fang, and Brian Knight. "Media bias and influence: Evidence from newspaper endorsements." The Review of Economic Studies 78.3 (2011): 795-820.). A paper by Maja Adena et al. (see Adena, Maja, et al. "Radio and the rise of Nazis in pre-war Germany." Available at SSRN 2242446 (2013).) showed the impact of media on the rise of Nazis in Germany which provide us a chilling reminder of the power media can wield in impacting our perceptions (remember Mein Kampf?). There are sections of media that constantly attempt to 'entertain' us, or rather distract us, and attempt to mold our perceptions. The 'talking points' on Iraq War where the Bush administration had a preplanned approach on how to influence public perception in support of the war is a good and a relatively recent reminder of that. So is the media campaign to present climate change as a 'green agenda.' It isn't too outlandish to believe that a similar PR exercise is underway to alter public perceptions about inequality that how fat paychecks (even in a recession) to few is 'good' for all or at least completely normal. Such an attempt to distract public opinion, and make them feel restive but silent, has a direct impact on people's ability to come together and take a stand. Thus the elite section of society believes the general public would soon get over their anger and settle for the status quo. However, there are new trends, the trend of social media, which is disrupting the current media oligopoly. Just recently Disney announced the acquisition of a major YouTube based production company, signaling the rising importance of internet media in the industry. As the media industry disrupts so will the zeitgeist, which leads us to an unknown territory. There is a reason to believe that as new media takes center stage, it will directly improve social capital in democracies, and spurt new civic engagement and make democracy more participative. However social capital can go the other way if in case people are unable to build cross-constituency social capital in time and amidst a zeitgeist of fear they barter freedom for security or violence. In such a setting such new media can promote radical ideas that take society towards the far left or right, directly threatening the democratic ideals of western nations. One should remember that the rise of Hitler too happened in desperate times right after the great depression of 1929-30 and was helped by the negative social capital of homogenous groups. We have also seen the rise of radical right parties in the UK in recent times. Similar is the rise of anarchist and communist movements which have become more vocal and active in the past few years which distrusts the electoral process. There is an increasing antipathy of people towards the Westminster or White House which are considered not edifices of democracy anymore but rather mouthpieces of the City and the Wall Street. If the first scenario of positive, participatory democracy plays out, there will be redistribution, the public will benefit, and the size of the rich will be cut down and constrained. If the second scenario of fear and retribution plays out, while the public may be ecstatic at the beginning, however soon hysteria will pave the way for oppression. New power cabals will get created, and most certainly the old will be dismantled. The status quo is unsustainable in a long run because it has been here for a long time and the zeitgeist demands change, and it is important that the existing power elite wakes up to this reality. While change is inevitable, the direction is not, but the greater the resistance from the elite to regulate itself, the sharper will be the response from the public. So, it is only prudent that the elite understands this, and as a precaution repositions itself, by being open to redistribution through higher taxes. It must take the lead from figures like Warren Buffet and Bill Gates to champion fair redistribution, and not act as gatekeepers of wealth. Leaders like Obama or Cameroon have no room for future error because they need to push an agenda which does not put the liberal democratic ideals of their nations under threat. They need to reclaim their nations from plutocracy and save their nation from the possible shift towards something worse. Leaders need to give their country back to their people. Originally published: http://prateekraj.blogspot.com/2014/09/why-times-ahead-may-be-tough-for-world.html?q=liberal |

Prateek RajPersonal blog. Views expressed are my own, expressed in personal capacity. Archives

May 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed